Since my last post included my ‘breaking news’ of learning that I would be able to teach a class, much has transpired. I have taught TWO classes, went for a short visit to another Singapore secondary school, and facilitated a workshop on using Desmos in mathematics classes. While it’s only been a few days, it seems like so much has happened. This is a LONG post…only those with fortitude will make it to the end. I think the next post will have a lighter topic. My loving and supportive husband says that he’s got his “Singaporean Food” post ready to go. If that’s more to your liking, check back again soon.

In the Sec3N2 (Secondary level 3, Normal Academic stream, group 2) class on Tuesday, I introduced the topic of completing the square. This can be a tricky topic to teach as it can be quite abstract for students. I consulted the textbook, which provided a class activity in which the students were asked to expand the perfect squares of several binomials, to note the “b” and the “c” in the resulting trinomial form, and to calculate (b/2)^2 for each expansion. All of the information was to be collated into a chart provided in the text. While I think the objective of the activity was to provide a visual and algebraic representation of the relation between the “b” and the (b/2)^2 needed to complete the square, it didn’t leave any room for students to do any of the sense-making in my opinion. The last column (calculate (b/2)^2) essentially asks students to evaluate without really explaining – or expecting the students to figure out – why the value needed to complete the square was (b/2)^2. I knew pretty quickly that this particular resource in the textbook did not support my teaching philosophies or practice in general. In the text, there were also some visuals provided in the form pictures of round algebra ‘discs’ (colored circles) that depicted the expressions. But those visuals fell short. The x^2 circles and the x circle and the unit circles were represented with the same size, only differing in color. While the framed arrays formed squares to show how the product of the binomials makes a square, it couldn’t indicate how the square was incomplete in the first place and what value was needed to complete it. I didn’t really like how the lesson was seemingly presented in the book, so I went in search of something else.

Luckily, Beth, my fantastic Northside colleague (#thenorthsideway), had recently found a Desmos activity that dealt with this very topic and emailed the link to the math department. This was last week and before I even knew I would need it. Talk about serendipity! I re-opened it, deleted a few slides, added some others, and then used it with the class. If anyone out there is interested, here is the link that will take you to the editable activity (you will need to activate and login to a FREE account with Desmos). It was created by Nerissa G. (don’t know her) and edited by mathycathy (don’t know her either) and then by me, and likely by many, many others.

I started the class by asking the students to agree that they had to interrupt me if my American accent made it hard to understand me or if I slipped into American English – like using “factor” instead of “factorise” or “parentheses” instead of “brackets.” I gave each of the students a small white board and dry-erase markers because we didn’t have laptops/devices for them to do the Desmos activity on their own. My plan was for me to project and click through the slides while students wrote their answers on the whiteboards. It was basically a low-tech technology integration. Next, I asked students what came to mind when I said “completing the square.” A few offered responses of “incomplete squares” and one student drew three sides of a square on his white board and said it was an incomplete square, then drew the fourth segment to complete it. I told him it was a great depiction of what we were about to do.

Then, I moved on to what I thought would be a quick pre-lesson assessment to check their readiness for the learning objective (shout out to another fabulous colleague Jill for making that last phrase and practice such a ‘given’ in our department). It revealed that some of the students could not properly square a binomial or factor(ise) a trinomial into a binomial squared. Students were writing that (x+3)^2 = x^2 + 9. Classic mistake – in the US and here. If I had know that this was the case, I may have created other slides that gave a similar pictorial representation of the ones I used in the activity. As such, we spent some time clearing up those misconceptions. After a few of these problems, I started the above-linked Desmos activity. I only got through 9 of the 16 slides because of the unexpected gaps we had to clear up, but students were getting it. Overall, I’d say it was still a successful lesson. The regular teacher picked up where I left off the next day because I had a short visit to another local secondary school on Wednesday. She reported to me that the students enjoyed the lesson and that it was easier “to explain why the coefficient of x has to be divided by 2.” And, they were eventually able “to complete the square without having to draw the actual squares,” which I had asked them to do while I was teaching. Because of the scheduling, they don’t have math again until Monday. The real test will be whether they remember how to complete the square on Monday.

I visited NBSS because the professor of the class that I am taking at NIE recommended to us students that we visit. The principal of the school is a former student of hers and she spoke highly of him and the school. I wanted to check it out. I chatted with the principal and the assistant principal, spending a good portion of our conversation talking about how difficult it is to get teachers to teach in a more student-centered way. I also visited a couple math classes briefly and talked with the math HOD and the School Staff Developer. I learned from the principal about his approach of caring for the students and setting high expectations for them. He’s done much to enhance the physical environment of the school, installing bright graphics in the sports hall, creating spaces for permanent art installations, including a “Great Wall of Yishun,” which is a mosaic decorated exterior wall of the school property. Students and teachers through the years have contributed to the mosaics. He commented that his goal was to make the school seem less institutional and more like a home. I think he succeeded. I could see that it was a special place for both students and staff.

On Thursday morning I facilitated a Desmos workshop for TSS math teachers and then later taught a Sec2 math class. Most of the math teachers either had never used Desmos or had very little exposure to it, so we started with setting up an account and playing with the graphing utility. I shared with them some paper-based activities that I developed before Desmos created the Activity Builder. I also transformed those activities into on-line versions for Activity Builder. We did one of those next. In the 50 minutes we had, we didn’t have much time for them to start to work on their own activities, but they got a foundation of the graphing utility and the Activity Builder. I encouraged them to search for activities, modify them and make them their own. I also directed them to the Desmos-created activities in the thematic bundles. I demonstrated how the Activity Builder allows teachers to monitor students’ answers, to use student answers for cultivating discourse, and to encourage students to read and respond to other students’ ideas. I reported that using the white boards could be a viable alternative because the students do not have laptops or Chromebooks. The feedback was positive, with some teachers wishing we had more time – a common refrain from any teacher!

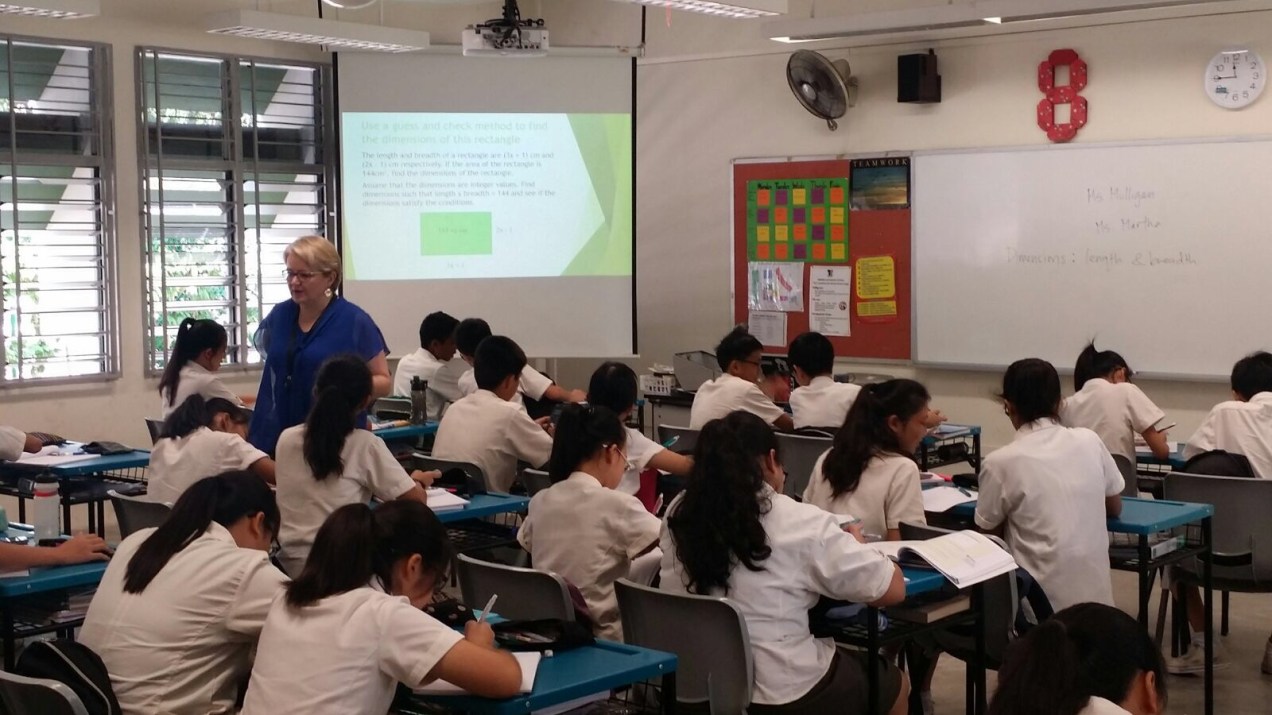

Directly after the workshop, I taught 40 Secondary 2 students (equivalent to US 8th grade). Wow. Talk about exhausting. Forty kids is a lot to handle. I had 60 minutes to teach “Solving Quadratic Equations by Factorisation” – starting with the zero product property. Again, I felt that it was my task to allow students time and space to make sense of these ideas. I couldn’t just tell them what they had to know. As much as I wanted to use graphs, I couldn’t attach the ideas to roots of a quadratic because the book doesn’t do that and keeps that as a separate topic. Therefore, I felt that using Desmos was not appropriate…unfortunately. After a challenge problem in which I encouraged them to use guess-and-check (and they didn’t *want* to use guess and check), I displayed the slide below. Predictably, they moaned when they saw there were so many problems to answer. Then, they chuckled when they realized what was going on.

The next slide asked a simple question:

I asked students to respond to the question and their hands went up. I called on one girl and she said, “Zero.” I said that answer was not enough, that I needed an answer that was equivalent to a paragraph, not just one word. “Please go on,” I said. She looked at me like I was a little crazy. Of course, I knew what she meant, and she knew that I knew what she meant, but I couldn’t let her get away with a one-word answer. After waiting for a bit, she said, “Each equation has a zero.” (I didn’t want to harp on the fact that they weren’t quite equations without the resulting evaluations included in them, so I let that part go.) “OK,” I said. “That’s a sentence. Let’s add on to that sentence to make a paragraph, which needs at least three sentences. That’s what I learned in the States, at least. Who wants to add on to that?” After another wait, some hands went up and one girl said, “In each equation, zero is multiplying another number.” OK, so we were up to two sentences, but we hadn’t fully explained what was happening. Finally, a boy proffered his sentence, “And when you multiply any number by zero, then answer is always zero.” We finally had a paragraph’s worth of an explanation. I made each of the students repeat their sentences in order about three times each.

Next, the students had to generalize (generalise) what they saw, so my next prompt said:

I asked them to write down some ideas and then they shared. Again, it took about three students to come up with comparable statements to the property below. I didn’t just tell them what it was; they had to tell me what it was.

The rest of the lesson proceeded with applications (or not) of the property and important discussions about the examples I provided. Some students struggled with the last example below (where the answer is x = 2 or x = -3). And, after some practice problems, some students were still struggling with what to do AFTER the factorization. I wasn’t completely successful at getting them to understand how to apply the zero product property once they got to the step where they needed it.

I’ve shared all this on this (extremely long) blog post for at least a few reasons. I was excited to teach and this blog allows me the chance to reflect on my teaching in a way that I cannot when I am actually teaching full-time. I wanted to explain at least a little how I espouse my beliefs about teaching and learning through my teaching practices. I hate to lecture. I hate to merely tell students what they are supposed to know. I want them to understand math, to make sense of it, to talk about it with each other. Explaining what I did and some of my choices allows me to offer evidence to my practice.

(Big thanks to Thomas for taking the pictures for me – even without my asking.)

I don’t hold the illusion that this post will change anyone’s teaching practice, but perhaps it will spark conversations between teachers who have read this (thanks for getting this far, by the way). As I told a colleague here, teaching is so isolating. Teachers rarely get to see other teachers in the practice of teaching. Videos in places like Teaching Channel are great resources, but it’s still not the same as seeing another teacher live. Every teacher I know agrees that the student teaching term is not long enough for most teachers to learn the craft. So, teachers need to make concerted efforts to see other teachers teach. New doctors don’t meet with patients on their own. New attorneys don’t litigate on their own. It seems like it’s only teachers who are left to their own devices as soon as they are credentialed. Perhaps this lengthy post will encourage a few teachers to think more about their own practice, to talk to others about their teaching and to see their colleagues in action.